Educators have done their absolute best with the resources available during the COVID-19 pandemic. They have turned in-class projects into virtual lessons, connected with students on a social-emotional level, and tried to keep up with the expected curriculum. As a whole, all of these efforts are impressive. However, missed content is still a concern.

How can states evaluate students to make sure they learned all of the required material? Furthermore, how can colleges rate students by their test scores when most SAT and ACT screenings were canceled?

During the pandemic, administrators and district leaders have been operating with the adage “never let a crisis go to waste” in mind. There have been calls for years to change our dependence on testing and student evaluation standards. This pandemic might be the turning point that states and school systems need.

COVID-19 Stopped Standardized Testing In Its Tracks

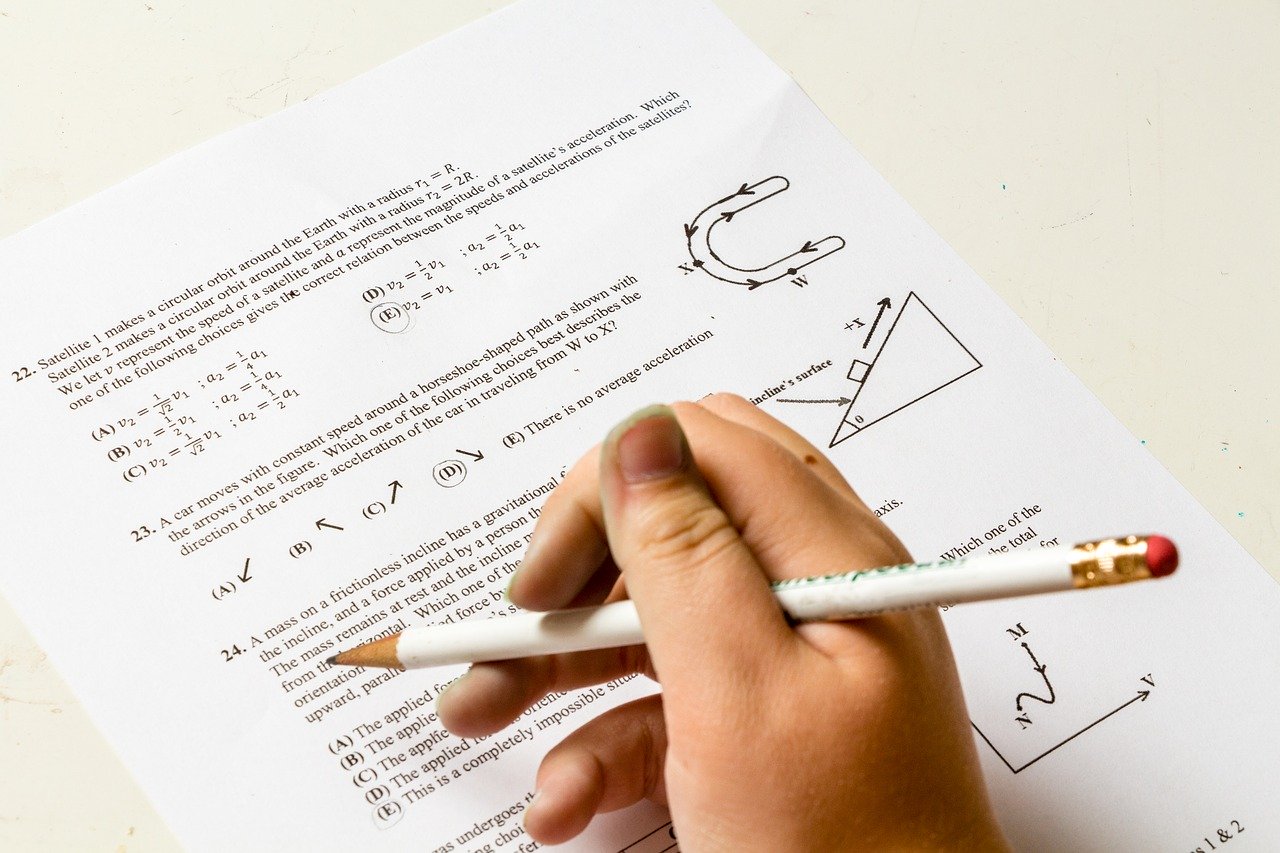

As schools closed across the country, testing as a whole was canceled. There was no way to ensure that students were tested fairly across the board and no way to ensure that they didn’t cheat. Everything from state evaluations of third-grade students to seniors taking the SAT ground to a halt. In the months since, many educators have called for the end of this testing as a whole or at least a reduction in testing for students.

A reduction of standardized testing needs to start at the K-12 level, but also needs support from institutions of higher learning. In 2020, both Cornell and Harvard College issued statements waiving the need for students to submit SAT/ACT scores in their applications. Two other Ivy League schools, Princeton and the University of Pennsylvania, had previously stopped requiring students to take those tests.

“While our policy has long been that SAT subject tests are recommended but not required, now seems the appropriate time to reiterate that applicants who do not submit subject tests will not be disadvantaged in our process,” wrote Karen Richardson, dean of admission at Princeton, in a statement.

If colleges reduce the importance of test scores, then some K-12 districts and educators may further reduce the number of tests students take in the name of “practice” for the SAT format.

There are other reasons to step away from the SAT/ACT tests. Reliance on test scores leads to inequities in higher education, says Reetu Gupta, CEO of college recruitment platform Cirkled In. “Even today, at-risk youth go to college at an almost 30% lower rate than typical kids, partially because they never take the test and never come on colleges’ radar,” she says. “Finances are not the primary reason for this gap.”

Interestingly, there might not be that many barriers in the way of reducing testing practices. In an article for the Washington Post, staff reporter Valerie Strauss says calls for standardized testing reforms have been largely bipartisan. President Trump has never advocated for increased standardized testing while Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden recently spoke out against high-stakes testing.

These beliefs trickle down. Without an advocate in the White House, governors on both sides of the aisle can freely speak out against these tests and take steps within local districts to reduce or remove them.

Standardized Testing Has Been Challenged for Years

One of the biggest issues with mass testing is understanding what the educational powers-that-be do with the grades. Test scores are used to evaluate schools and the teachers themselves. Some districts even tie test scores to tenure qualifications, which impacts teacher pay. Several teachers have pushed back against this “performance-based pay” system because it creates more inequities and doesn’t actually highlight the value an educator provides students.

“If teachers feel that a new performance-based pay system is being imposed upon them from distant legislators who do not understand the realities of a classroom, they may feel disenfranchised and resentful, which could ultimately have negative results for their students,” Grace Chen writes at Public School Review.

Plus, if teacher pay is based on test performance, then the educators getting bonuses and pay raises are likely already in high-income areas, where parents can afford to hire tutors and where teacher salaries are higher at the outset.

Some teachers feel reduced to a level where they have to “teach to the test,” or direct all of their education hours toward preparing students for standardized testing.

“Since teachers face pressure to improve scores and since poverty-stricken students generally underperform on high-stakes tests, schools serving low-income students are more likely to implement a style of teaching based on drilling and memorization that leads to little learning,” writes Hani Morgan, a professor of education at the University of Southern Mississippi.

While high-income schools have more resources to attend field trips and participate in project-based learning, low-income students are left with rote memorization. This hardly fosters a love of learning and a curiosity about various school subjects.

Teaching to the test also makes teachers focus on subjects like math and reading, causing them to spend less time on subjects related to science, history, art, and other engaging material. However, studies have found that focusing just on those subjects don’t necessarily lead to better test results.

“Too many American schools are actually misreading their situation: the best way to help students do better on standardized math and reading assessments might well be to spend less time teaching these subjects in artificial isolation,” Conor Williams writes for The Century Foundation.

Students hone their reading, math and comprehension skills when they engage in problem solving and group projects, not when they are told to sit quietly and memorize.

Testing and the Common Core Face Similar Criticisms

The issue that teachers have with the current teaching format isn’t just because of testing. They also look at state and national standards (like the Common Core) which restrict what they can cover. There’s no time for tangential material that can engage students when you are so focused on hitting each of the Common Core requirements.

Education reporter Dana Goldstein wrote an impressive article at the New York Times that addresses the inception of the Common Core standards, the reactions to it, and its successes and failures. At one point as many as 40 states had adopted the standards, which were going to unify education across the country. A student in Idaho would learn the same material the same way as a student in Brooklyn.

Essentially, Common Core standards set a “one-size-fits-all” approach to learning by mandating that students learn the same content in pretty much the same ways.

“Any educator worth her salt knows that students learn in different ways and that education needs to fit the needs of the student, not the reverse,” writes Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D., executive director at the American Institute for Learning and Human Development. “The Common Core is all about foolish consistency and runs a super-freeway through all the little hills and dales of student individuality.”

This way of teaching implies that one way of learning is the best way. Asking students to learn multiplication in one specific way discounts individual learning styles and the many ways of thinking about math.

“Common core is not about getting you an answer most directly,” Leticia Chavez-Garcia writes at La Comadre, an education advocacy resource based in Los Angeles. “It’s about how you can break down difficult problems into smaller simpler problems by using methods that you, yourself, know how to use best.”

The Common Core processes can actually slow students down and confuse others.

Some States Have Adopted Common Core Alternatives

In the past few years, some states have looked to step away from Common Core Standards. Surprisingly, the replacement of the Common Core standards is another instance where politicians on both sides of the aisle agree. However, the two parties differ as to what should be done about it.

In 2019, the Alabama State Department of Education voted to replace Common Core math guidelines with new standards developed within the state.

“We painstakingly researched, reviewed, and analyzed every single standard within the course of study,” said Suzanne Culbreth, a 2013 Alabama Teacher of the Year. “We accepted and revised our work based on public comment and suggestions from experts in math education. These are Alabama standards, developed by Alabama educators, for Alabama students.”

In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis debuted the BEST Standards (Benchmarks for Excellent Student Thinking) to replace the common core. The goal, according to Richard Corcoran, commissioner of education, is to create “excellent thinkers” while standardizing how courses are taught.

“When you’re trying to remember what’s four times four, and you have to think about it and it’s not automatic, you’re never going to be able to conquer algebra and all those other courses,” Corcoran says.

However, some educators worry that state-developed standards might not be the right solution. These standards are often developed quickly to meet calls by the governor and don’t have time to be thoroughly evaluated before they are used. In Florida, some teachers have called the new guidelines vague and hold students to “weaker” standards.

“This lowering of expectations will lead to gaps in our students’ learning,” says professional development specialist Pamela Ferrante of Seminole, Florida. “These changes are a step backwards.”

Breaking up the Common Core standards with state-developed guidelines will also make it harder for the federal government to determine which states and counties were most negatively affected by the school closings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Along With Tests, Grading During COVID-19 Isn’t Fair

If colleges aren’t looking closely at SAT/ACT scores this year (and potentially in the future) and educators aren’t “teaching to the test” as much because of the diminished SAT use and rejection of federal Common Core standards, then how can teachers evaluate students? The answer lies in grading. However, this too is in a state of upheaval during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In April 2020, the Los Angeles Unified School District announced that no students would receive a failing grade for the spring semester. Educators deemed it unfair to potentially fail students in the midst of a pandemic when their learning process had been interrupted and then radically changed.

“Many of the examples we see of successful video learning have a significant selection bias,” Austin Beutner, the L.A. Schools superintendent says. “Affluent families with resources at home, schools with years of training and limitless budgets and students with demonstrated aptitude to learn independently.”

A set of guidelines put out by the Crescendo Education Group recommends using pass/fail grading during the COVID-19-related school closures only instead of traditional numerical or letter grades. They also recommend making these grades temporary.

“Schools should explicitly frame the grade as a temporary description of what a student has demonstrated based on incomplete information,” they write. When school resumes, students should be given the opportunity to prove that they have learned the material and receive an updated grade.

In a way, eliminating grades or reducing them to pass/fail options during this time may help teachers and school systems provide more equitable education and reduce their burden to maintain strict standards levels to keep up with test score expectations.

“If schools do require graded work from all students, they are expected to support certain student groups, such as homeless students, students with disabilities and English language learners, to make sure they have equitable chances to participate,” writes Kristen Taketa, K-12 education reporter for The San Diego Union-Tribune.

If schools can’t provide those resources, they have no business demanding high grades and test scores from students.

Educators have challenged the Common Core, grading practices, and excessive standardized testing for several years. However, the COVID-19 has given districts an opportunity to make drastic changes. Short-term solutions now (like canceling standardized testing) could lead to long-term best practices in the future. This pandemic can be an opportunity to reset and change how students learn — for the better.

Images by: racorn/©123RF.com, lopolo/©123RF.com, tjevans, jarmoluk

What do you think?